Ten Books, One Voice, and a Lot of Truth: The Work of S P Clark

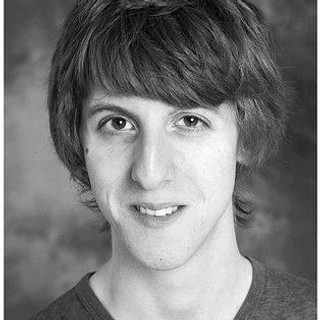

- Simon Clark

- Feb 6

- 4 min read

I never set out to write ‘a body of work’.

I wrote because there were things sitting inside me that would not stay quiet any longer – things that did not fit neatly into conversation, small talk, or polite versions of myself. Writing became the place where I could stop editing, stop explaining, and stop pretending I was fine when I was not.

Under the pen name S P Clark, I have published ten books so far – poetry, short stories, and a play. On paper, they look varied. In reality, they are all part of the same long conversation: about what happens to us, how we carry it, and what changes when we finally say things out loud.

Much of this began after something happened that shifted how I moved through the world.

Ten months later, I finally said the words aloud: I was raped.

What followed was not clarity or release. It was not brave or empowering. It was confusing, exhausting, frightening – and deeply lonely. One Year With Mister R came out of that space. I did not write it with hindsight or wisdom; I wrote it while I was still trying to understand what my life had become. The poems follow that first year chronologically, because that is how it felt – one day at a time, sometimes minute to minute. Mister R became an unwanted lodger in my life, always present, shaping everything.

There is often an expectation that stories like this should move quickly towards healing. That there should be an arc. A resolution. Real life rarely works like that. Three Years Underneath Mister R exists because the story did not stop after twelve months. Trauma does not politely disappear once time has passed. It lingers, changes shape, resurfaces when least expected. Writing across three years allowed me to show that reality – the setbacks, the slow shifts, the moments where hope appears quietly rather than triumphantly.

But these books are not only about pain. They never were. Love has always been part of the story too – sometimes arriving unexpectedly.

Two Men, One Love grew out of a connection that was never meant to be serious. A one-night hook-up on my fortieth birthday turned into something deeper, more intense, and ultimately short-lived. The poems do not protect either of us. They hold sex and tenderness, vulnerability and heartbreak side by side. It felt important to honour that love without diminishing it simply because it did not last.

Earlier love appears in The Journey to Love, which looks back at a relationship in my twenties. Set over a handful of days, it captures the intensity of early love – desire, excitement, the belief that this person might be the one. Reading it now, there is a softness to it, not because it was naïve, but because it belongs to a time before experience taught me to be careful.

As I continued writing, I found myself repeatedly drawn to subjects many of us are taught to avoid. Death, for one. Entertaining Goodbye does not try to make it easier or more palatable. It simply sits with it – illness, suicide, grief, the quiet awareness of our own mortality. If there is hope in these poems, it comes from honesty rather than reassurance. Sometimes naming something is the first act of kindness we can offer ourselves.

Art became another way in. In Clark Meets Munch, I used the titles of sixteen works by Edvard Munch as starting points – not to analyse the art, but to respond to it emotionally. Munch was already exploring melancholy, sexuality, puberty and mortality. The poems grew out of recognising that shared emotional territory across time.

At the other end of the scale is Haiku, a quieter collection written over many years. These poems are small, but they are not slight. They notice the planet, bodies, pleasure, depression, pain – moments that might otherwise pass without remark. Sometimes a few lines are enough to say what a page cannot.

That interest in precision runs straight into Sixty, a collection of sixty short stories, each exactly sixty words long. The constraint was deliberate. I wanted to see how much could still be said when there was nowhere to hide. Within those limits, whole lives unfold – sometimes dark, sometimes absurd, sometimes unexpectedly tender. Brevity, it turns out, does not reduce impact; it sharpens it.

The Unknown Lady allowed me to widen the lens again. It is a story about grief, but told through fragments – other people’s perspectives, assumptions and projections. At its centre is a woman who is constantly observed and rarely understood. Writing it returned me to a question I keep circling: how well do we ever truly know the people closest to us, especially once loss enters the room?

The only piece written for the stage, Discovery, brings many of these threads together. It centres on a young man coming to terms with his sexuality inside a household shaped by emotional abuse and fear. Secrets surface, tensions escalate, and silence becomes impossible. It is uncomfortable in places – deliberately so – but it also leaves room for resilience, for change, for the possibility that truth, however painful, is still worth choosing.

Looking at these ten books now, I do not see separate projects. I see a record of someone trying to live honestly – through trauma, through love, through grief, through moments of connection and loss. I see writing used not as performance, but as a way of staying present.

You do not have to read all ten. You do not have to read them in order. You can dip in, step away, come back later. But if you have ever felt unseen, unheard, or unsure how to name what you have lived through, there may be something here that resonates.

They were not written to impress.

They were written because some things do not let you stay silent.

Comments